MOLINE, Ill. — Missing out on the big snow or seeing nothing on the radar over the Quad Cities while the rest of the area is experiencing heavy snowfall, could a "weather bubble" be causing this? Let's explore this popular Quad Cities theory.

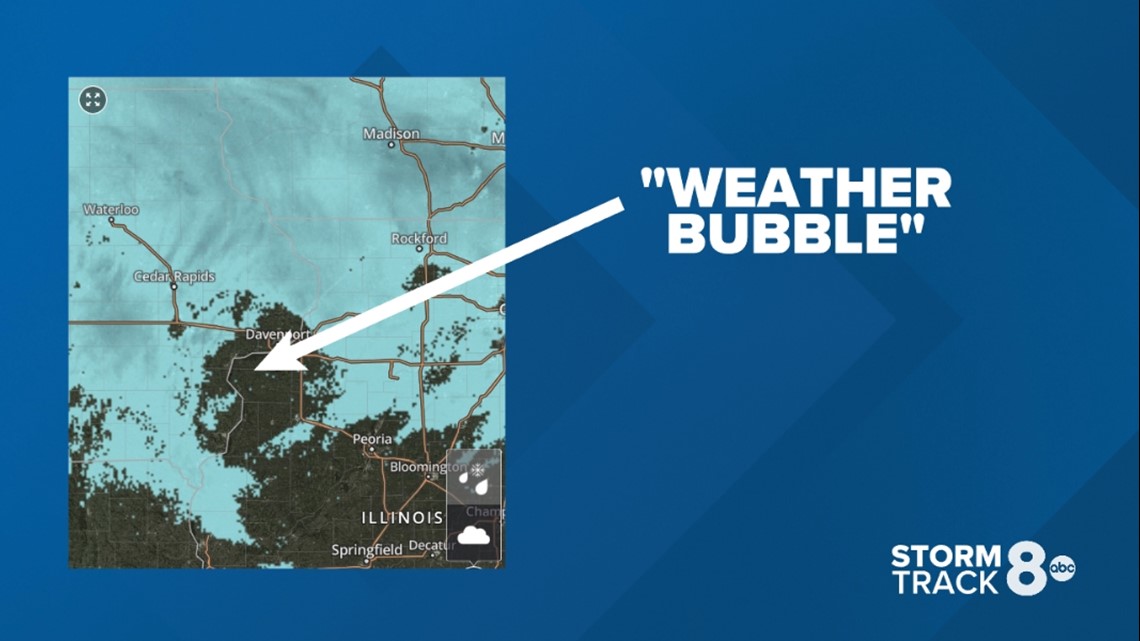

Take Saturday, Jan. 22 as an example. The radar image above from our very own Storm Track 8 Weather app shows a good amount of snow falling across the region. However, you'll notice a large gap in the coverage located right over the immediate Quad Cities area. Could this be the infamous "weather bubble"? Not quite. Here's why.

Doppler radar is a complex theory that involves a lot of moving parts, quite literally. At this particular time on the radar image, it is true that widespread snow was occurring in the region. However, there was also a layer of dry air present right over the immediate Quad Cities that prevented any snow from reaching the ground until a process referred to as "saturation" was complete. This layer of dry air typically eats away/evaporates any precipitation falling through it from above, in this case, snow.

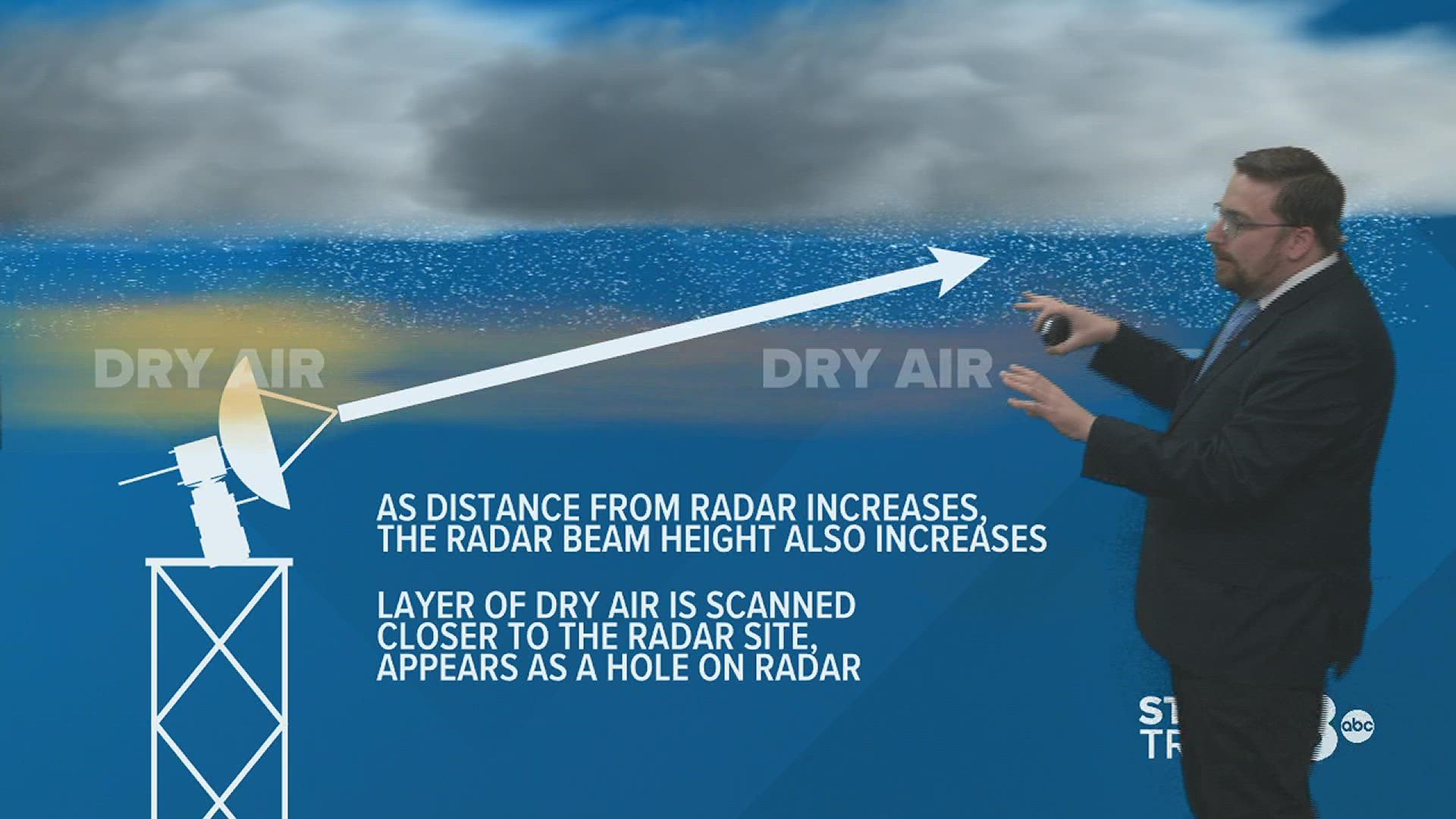

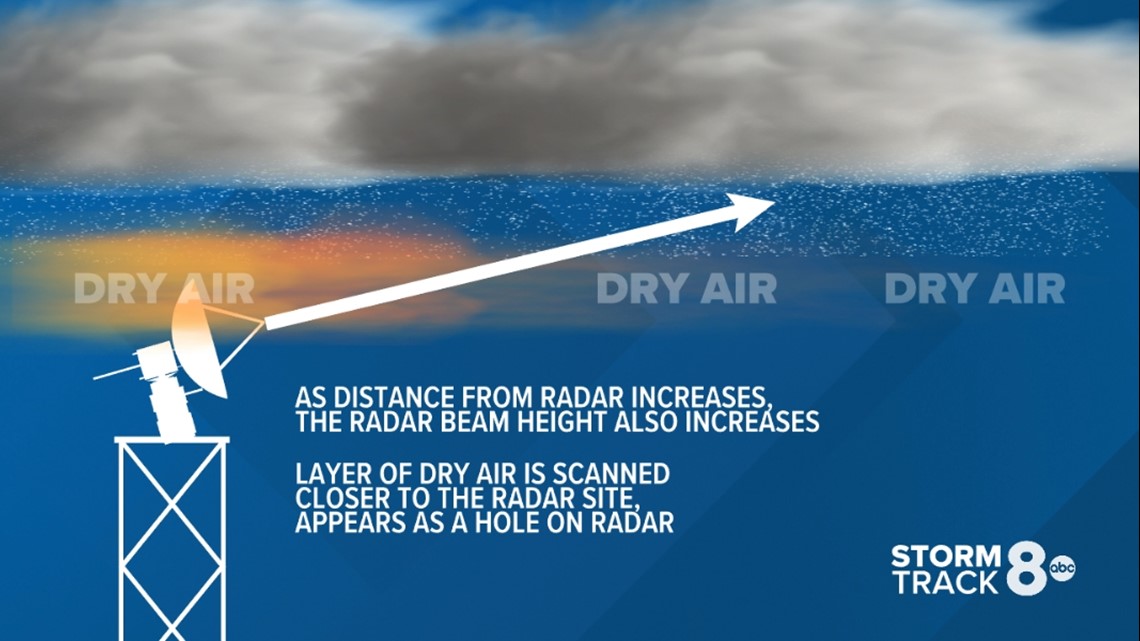

Doppler radar works by sending pulses of energy and then listening for those pulses to return back to the radar dish after they bounce off some type of precipitation, whether it be rain, snow or ice crystals.

Because the Earth is round, the radar beam will shoot higher into the sky as the distance increases from the radar. As you can see in the example above for this scenario, the area immediately surrounding the radar is not picking up any snow that is falling higher up in the atmosphere due to a layer of dry air in place. However, the further out the radar beam goes, the more "snow" it is able to pick up because the beam is aimed much higher into the clouds themselves, above that level of dry air.

In times of severe weather during warmer months, you'll often hear us mention rotation being "too far away from the radar to get a good reading." The same concept applies here, too. Severe storms exhibit the strongest rotation at the lower level, and once a storm travels a considerable distance away from the radar site, we are not able to "scan" those lower levels because the curvature of the Earth means the radar beam is actually scanning much higher into the storm itself.

Check out one of our Storm Track 8 University lessons on Doppler radar below to learn more about how this technology works.

Part two of this question involves the Mississippi River. Many of you have commented and wondered why storm systems seem to either split or die off after they approach the river itself. I'll be answering this question coming up on Monday, Jan. 31.