DAVENPORT, Iowa — The Putnam Museum and Science Center has hundreds of artifacts in its possession and a mission to preserve history and educate the public. It also has one lesser known job: to return Native American artifacts back to home.

"When the Europeans first got here, they discovered these burial mounds and they were like, 'oh this is wonderful' and there was this huge controversy over where these burial mounds came from," Putnam Museum and Science Center Anthropology and History Curator Christina Kastell told News 8's Collin Riviello. "So they started digging into the burial mounds."

The act of returning these artifacts back to Native Americans is called repatriation, and a 1990 law by the U.S. Government called the Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act.

According to the National Park Service, "Once lineal descent or cultural affiliation has been established, and in some cases the right of possession also has been demonstrated, lineal descendants, affiliated Indian Tribes, or affiliated Native Hawaiian organizations normally make the final determination about the disposition of cultural items."

In essence, the Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act created a process whereby Native American could try to recover lost remains.

"Unfortunately, back in the 1800s, so much got taken away from the Native Americans and the government didn't want them to practice their native religions. And so now, this is an effort by the government to help restore nations and make them whole," Kastell said.

Kastell says she's been working for two decades at Putnam, reaching out and making available any remains it has. In total, she says about half a dozen tribes have reached out to the museum since 2000.

"If all of your history were taken away from you, you become sort of like a lost nation. A lot of what we do is provide the location where [the remains] came from, and then the tribal nations, as they start reviewing their history and start their own NAGPRA process, track down where their people have been," Kastell said.

Once a group reaches out to the Putnam, Kastell says she creates a tiered list for them indicating which remains she believes belong to them, which might belong to them, which likely don't belong to them and which may belong to them.

"We've had several tribes that we've got tiered lists out to, that we've heard nothing back from. So either there's nothing that they believe is relevant for them, or their system is just moving slow," Kastell said.

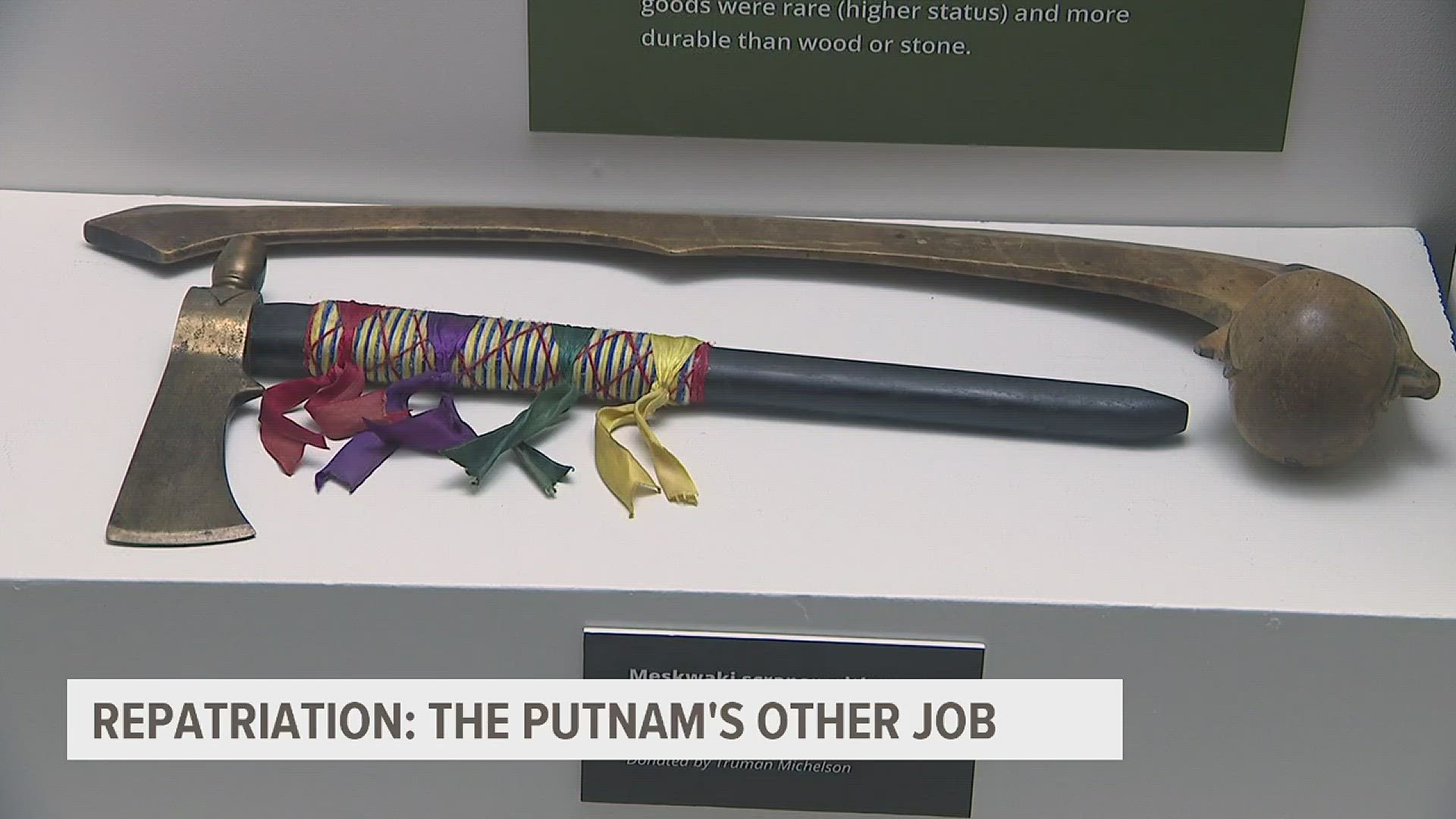

She says right now there is one nation claiming patrimony for five objects at the Putnam.

"They have just been deaccessioned from our collection, and [we] are waiting for them to make arrangements to come pick up them up," Kastell said.

Finding a match isn't always filled with fanfare.

"It's like when you are going through objects left behind when somebody in your family dies, it's not a great big party," Kastell said.

However, it's still an important moment for Native Americans and for the museum.

"It makes me feel very proud to have been able to be the holder of these objects and then to be able to actually return them to people who are going to cherish and honor them. When we hold objects here at the Putnam, whether it be objects or human remains, we treat them as we would want to be treated and we treat them as the nations would like to have them treated," Kastell said.