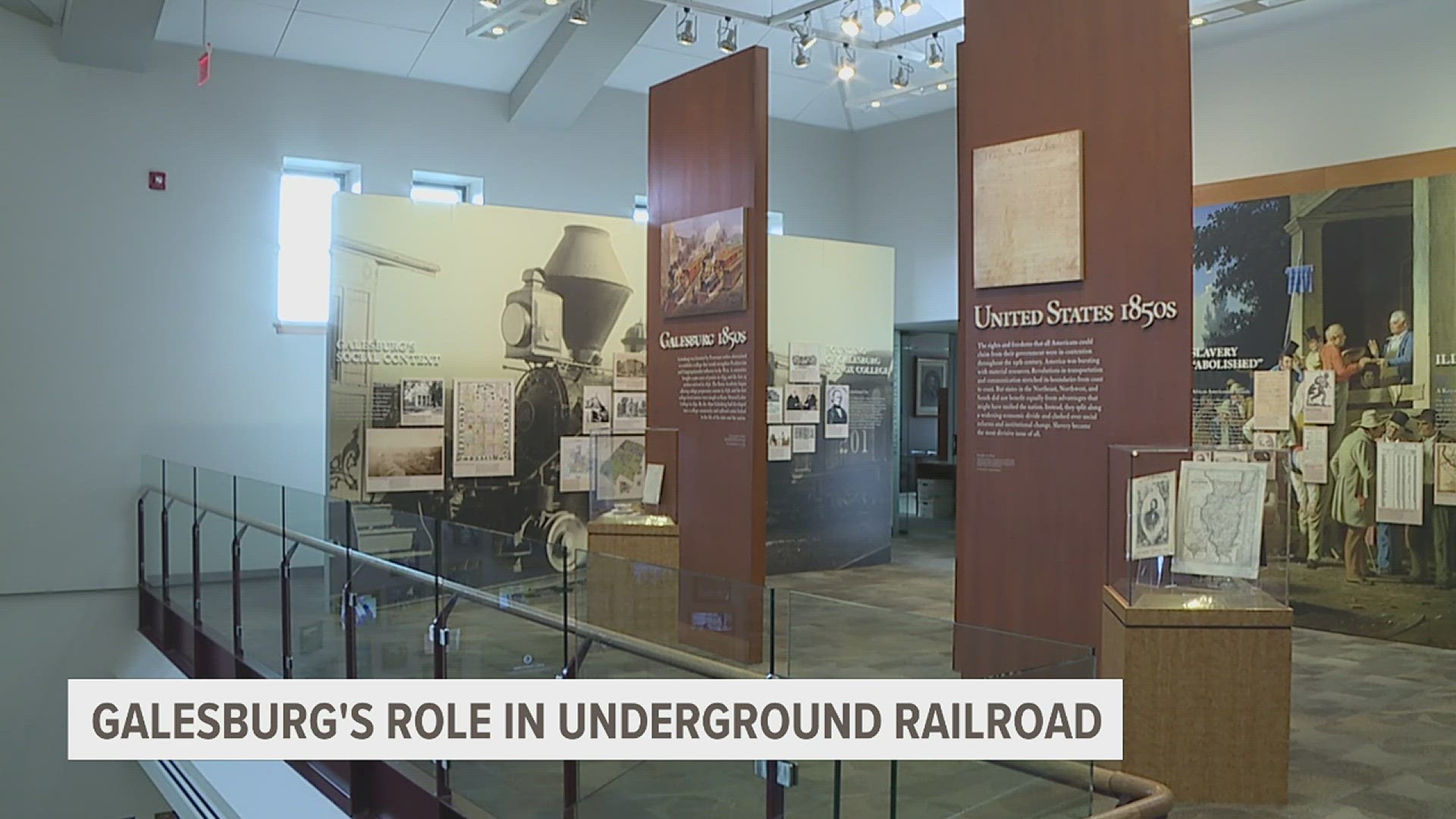

GALESBURG, Ill. — On the third floor of Knox College's Alumni Hall, the Underground Railroad Freedom Center stands as a testament to the college's and Galesburg's history and the role both played in the anti-slavery movement.

Both Knox College and Galesburg were founded in 1837 by anti-slavery advocate George Washington Gale, who came to Knox County from upstate New York. According to the center, Galesburg was considered unique because the overwhelming majority of the people who lived there for the first 20 years were opposed to slavery.

"These people when they arrived, were already what you'd call radical abolitionist, and really, from the beginning started to be involved with helping fugitive slaves escape northward," director Owen Muelder said. "Missouri is only about 90 miles from Galesburg and so fugitives fled out of Missouri and also from states deeper south. Also, a number of enslaved people were used on river boats and barges. Many of them escaped off the river and came in this direction."

Galesburg became one of the primary locations on the Underground Railroad "Quincy Line" on the way to Chicago. Princeton was part of that too.

"Galesburg gained a reputation almost from the beginning as a really important Western anchor of the abolitionist movement and involvement with the Underground Railroad," Muelder said.

There are few records about just how many people escaped to freedom through Galesburg. In Samuel G. Wright's diary, it's suggested he had aided 21 slaves by 1842. Wright was a Knox College trustee.

Another Knox College trustee, William J. Phelps, lived near Elmwood, Illinois. It's believed a barn on his farm was most likely used as an Underground Railroad signal station. According to the Knox College Underground Railroad Freedom Center, when lanterns were lit in the barn attic, the glowing cross he had carved at the top signified that it was safe for fugitive slaves to head northward.

"In addition, it was not unusual for a fugitive slave or two or three who were being aided to be taken outside Galesburg and hidden outside the city, maybe at night brought back in to be fed and aided, in case slave trackers came into town to try to catch slaves," Muelder said.

Some places in Galesburg that were stops on the Underground Railroad no longer exist today. Muelder said fugitive slaves were hidden in the bell tower of the old Beecher Chapel. Others would simply hide in Galesburg's surrounding prairie terrain. During the summer to fall, big Bluestem grasses grew to six, six-and-a-half feet tall.

"Fugitive slaves could literally pass through this prairie grass," Muelder said. "Those timber groves usually were on slightly higher ground where they could hide in the timber, look back through the prairie grass and decide whether it was safe for them to move on."

One of the most famous fugitive slaves in Galesburg was Susan Richardson. She was enslaved by a man named Andrew Borders in Randolph County, Illinois when she and her three children escaped to Knox County in 1842, but after her escape, they were captured and taken to the old Knox County Courthouse in Knoxville.

"(They) argued that there was no proof that her owner who had come to get her and the children really belonged to him," Muelder said. "He had to go back to Southern Illinois to get evidence."

This legal battle continued between 1842 and 1844. Ultimately, Borders took back ownership of the kids and Richardson was hidden in Galesburg, despite her desire to be with her children. Abolitionists informed Richardson of the potential realities she could face if she went back to them, including the potential for her to be sold or seen as a threat.

Susan Richardson went on to become involved with the Underground Railroad in Galesburg and helped establish the city's first Black church. She lived into her 90s and passed away in Chicago in 1904. She is buried in Galesburg's Hope Cemetery.

In 2021, the old Knox County Courthouse was recognized on the National Park Service's National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program.

One man Richardson helped escape northward through Galesburg was named Bill Casey.

"He returned to Galesburg a few years later, and he was working at a job outside of town when two slave trackers came to town," Muelder said. "Asked a little young Black boy if he knew where Bill Casey was. The story goes that this little kid said no, I don't know where he would be. And after they rode off into another part of town, he went north and warned Casey to get away. So I think there was a consciousness on the part of many people to come up with a lot of imaginative ideas about how to make sure fugitives were not caught."

In 2006, Knox College's center was recognized by the National Parks Service as a Network to Freedom research site.

The college's foundation and its rich history with the abolitionist movement is something to lean into, President C. Andrew McGadney said.

"I think history is one of those things that we should all kind of lean in on, we should all respect it," he said. "But if you don't actually go out and kind of live it and show it, people easily forget about it. And so part of what we're trying to do here is not only show it, put it on display, but we want everyone to lean it to see not only the founding of the college, but then what we continue to do with that history... It's a college that does not have to go back in history to change things or try to identify buildings or issues where dollars to create institutions for higher learning had issues behind it that were negative."

Muelder hopes that people can look at these exhibits and documents and learn about the role Galesburg played and the journey Black people seeking freedom took.

"The great flaw, more than anything else in our society, was the fact that on the one hand, we set up as an example to the world life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness and freedom," he said. "And on the other hand, at the same time, slavery was allowed to exist. So I think making sure that each generation, particular of young students, gets that story straight, is important for understanding who we are and how we got where we are today."

The Knox College Underground Railroad Freedom Center also has an exhibit on the Lincoln-Douglas debates in their campaign for a seat in the Senate in 1858. The fifth debate was held in Galesburg on Oct. 7, 1858. Old Main on the Knox College campus was designated a national historic landmark by the United States Department of the Interior for hosting that debate.

Watch more news, weather and sports on News 8's YouTube channel