MEMPHIS, Tennessee — When thousands of visitors descend on the quiet city blocks around the National Civil Rights Museum for the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., they’ll be walking over hallowed ground in the civil rights struggle.

Use the video player above to take a 360-degree tour of the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, or click here.

The museum, which tells the story of African-Americans from the Middle Passage to the present, is located at the Lorraine Motel — the place where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spent his final hours.

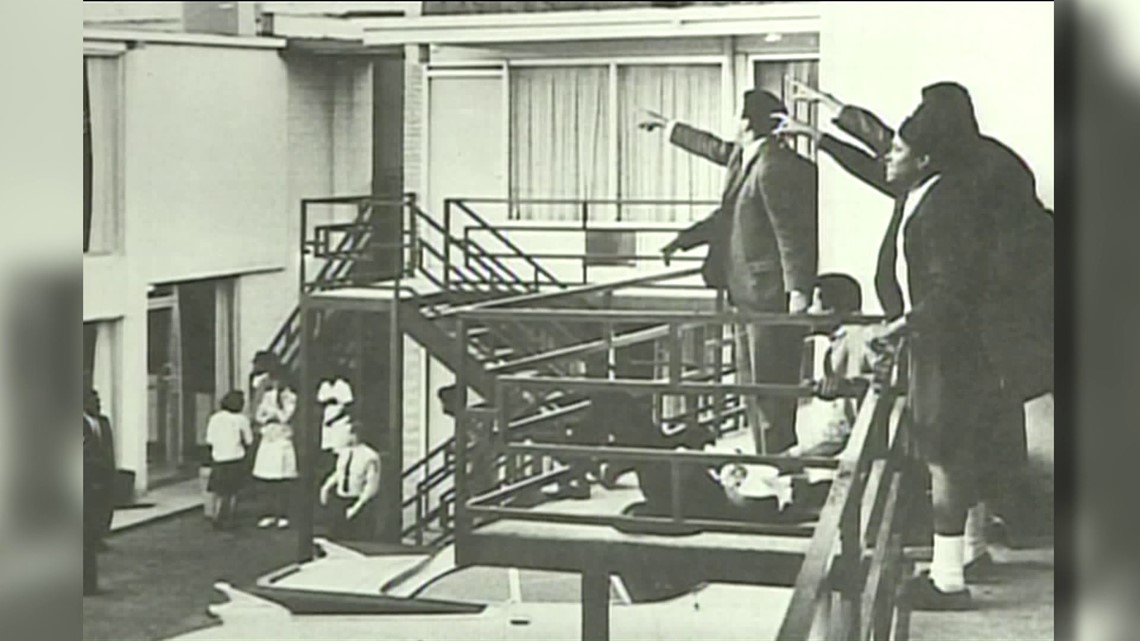

“What’s unique about our museum is that we are actually a historic site,” said Noelle Trent, director of interpretation, collections and education. “We are a site where history happened, so you can go out in the courtyard and you know you are standing in the same place where Dr. King and Jesse Jackson, Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young, all stood.”

The motel was built in the 1920s and in 1945, Walter and Loree Bailey purchased it, naming it after Mrs. Bailey and the Nat King Cole song “Sweet Lorraine.” Located one block off Main Street, it quickly became one of the premier destinations for African Americans — including Jackie Robinson, Sam Cooke, Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin — to stay in segregated Memphis.

King had stayed there during a previous visit in 1966. In 1968, he returned to Memphis to support a strike by city sanitation workers and lead a nonviolent march.

“A defining moment for the civil rights movement is the Memphis sanitation strike. And while it’s not known very well outside of Memphis, it is a key moment for us, more than just the moment when Dr. King was assassinated,” said Trent, standing just outside a museum exhibit chronicling the event.

Memphis sanitation workers in 1968 could work 80 hours a week, and still be on public assistance. They didn’t have uniforms and were sometimes refused rides on public transit because of their smell, she said.

Rev. James Lawson, a pastor in Memphis who was a King associate and leader of nonviolent sit-ins and protests, led the workers. During one speech, Lawson told them, “You are human beings. You deserve dignity. You are men.”

That phrase became the well-known sign worn by workers on strike: “I Am A Man.”

For weeks, they met at Clayborn Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church on the edge of Downtown, walking to City Hall several blocks away to demand their rights.

Trent tells the story of King’s last days: It was Lawson who called his friend King to come to Memphis and support the workers. King led a march, but it erupted in violence and King was whisked away, vowing to return.

When he came back to Memphis on April 3, a major storm raged outside. King thought the weather would drive away most of the crowd, but more than 2,000 people packed nearby Mason Temple to hear him.

Ralph Abernathy rushed to a phone, called King and asked him to come to the church. King jumped in a cab and delivered what’s now known as his “Mountaintop” speech — a totally improvised speech that would be his last.

The next day, King was killed on the balcony in front of Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel.

After 1968, the motel fell into decline and went into bankruptcy. It was reborn as the National Civil Rights Museum in 1991.

But the Memphis connection is just part of the story at the museum, which chronicles the movement through bus boycotts, sit-ins, voter drives and marches, told through the lens of ordinary people who went to extraordinary lengths to stand up for equality.

A new exhibit running April to December will reflect on how historical events of 50 years ago connect to events happening today — from the Poor People’s Campaign to the Occupy movement, from the sanitation worker’s strike to the Fight For $15 protest.

“Our memory of Dr. King tends to stop after 1963, but he continues to evolve,” Trent said.