After serving 30 years in prison for murder, the odds were stacked against 50-year-old Steven Crowley.

To this day, Crowley, a native of Cook County, Illinois, gets emotional discussing the night that forever changed his life.

His sister, who Crowley said was worried about the stigma associated with people who have been raped, refused to come forward to police with what had allegedly happened.

Crowley was only 19 years old when he was found guilty of murder in 1984. After his sentencing, he made a promise to the judge.

"I actually told the judge that I'm going to come out of here a better man," Crowley vowed.

Crowley found himself in a sink-or-swim situation. He could do his time - which would be 30 years instead of 60 because of day-for-day credit in Illinois - and hope to land a job once he was released. Or, he he could use every tool available to better himself.

Crowley chose the latter of the two.

While incarcerated, Crowley studied vigorously, earning associate's and bachelor's degrees. But, he says what he learned at the Dixon Correctional Center intertwined his passion and skill, and ultimately led to Crowley's second chance at life.

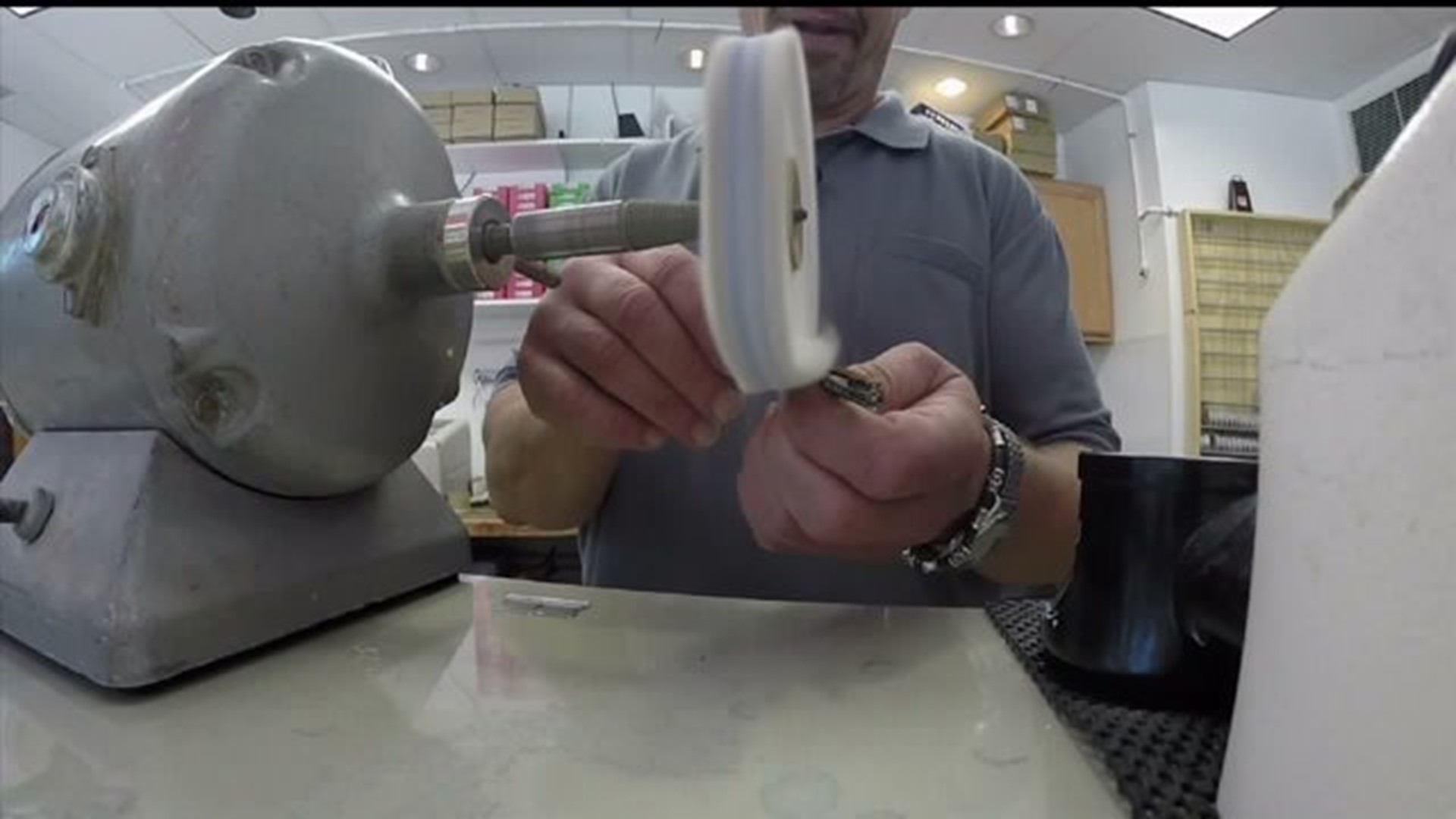

Behind the barbed wire fences and concrete walls at the Dixon Correctional Center, hides the prison's optical lab. That's where Crowley found his passion for crafting sight.

One hundred inmates work at the lab, producing about 1,800 pairs of glasses each day, and approximately 350,000 pairs of glasses each year, according to Christopher Melvin, the superintendent of Dixon's Correctional Industries. The glasses are manufactured for Illinois Medicaid patients.

Optometrists send prescriptions to lab, and the glasses are made from scratch. The glass itself, in its initial stages, looks similar to a clear hockey puck.

The lab contains several inmates who are certified through the American Board of Opticianry. Inmates who decide to take the ABO test must study for several months before the exam. The certification qualifies inmates to compete with other certified opticians for jobs.

Dixon Optical Lab has the highest ratio of certified opticians in their lab than any other lab in the state of Illinois, according to Melvin.

"I feel a sense of accomplishment that we are really getting our bang for our buck when doing this," Melvin said.

The team's foreman is Shawn Manuel, who has been incarcerated for 17 years.

"Coming in, I didn't know anything about lenses. You know, I learned like everybody else," Manuel said.

Once released, Manuel has plans of opening his own optical lab, and he's not the only one.

Tirzo Garcia, who operates as one of the lab's problem solvers, will likely be deported to Mexico upon his release. Since he will be back in his home country, the ABO-certified inmate has plans to open his own lab, and to import and export between Mexico and the United States.

Some inmates say the optical lab is a dream builder, allowing them to develop a skill and prepare them for when they are released back into society.

Steven Crowley said he is a living example of how the optical lab at the Dixon Correctional Center changed his life. Today, he is a successful optician at Corner Eyecare in Glenview, Illinois, about 14 miles north of downtown Chicago. He has a stable income, goals of opening his own lab, and the vision of helping other inmates who are released and have worked for Dixon's optical lab.

"Ideally, I would like to open my own lab and hire ex-offenders for that," Crowley said while standing inside the lab he works in today.

Crowley is living proof that no matter what circumstances arise, when a vision and an opportunity are presented, no dream is out of sight.