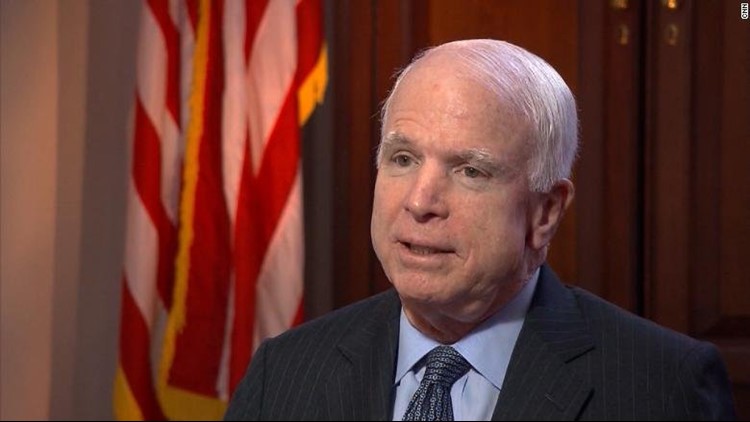

(CNN) — John Sidney McCain III was as complex as they come.

Stubborn and flawed, he survived many a brush with death and spent a lifetime trying to live up to the larger than life characters he idolized, both real and fictional. Until the end, he was still a hot dog fighter pilot with a dramatic flair. Quick to anger, but equally quick to forgive and always eager to share a laugh. He cherished his family and was unusually open with the depth of his love for his friends. A towering figure despite his less than towering stature.

The John McCain I first started to get to know in earnest was the one who had just returned to the US Senate after losing the 2000 Republican presidential primary.

I was a CNN producer then, and though I had been in New Hampshire in and around the famous Straight Talk Express, I mostly covered the Democratic side of that 2000 contest — Bill Bradley versus Al Gore.

Back in the Senate, the McCain I encountered was understandably smarting from the vicious and personal way fellow Republicans went after him and his family in the South Carolina. His loss there pretty much sealed his fate — and now he was in full maverick mode. That meant diving into work on several bills with Democrats that most Republicans hated. The top of that list was campaign finance reform.

It was the first real legislative fight that I ever covered in the reporting trenches on Capitol Hill. Looking back, I learned so much watching McCain dart around the halls of Congress, working alongside his Democratic partner, Russ Feingold, and sparring with his arch enemy on the issue — Mitch McConnell.

McCain was so passionate and determined, but he was also practical. He understood what a heavy lift it was to get a 60-vote, filibuster-proof margin on something that lawmakers feared would hurt their ability to campaign to keep their jobs. I lost track of how many times they compromised on a sticking point, thought they were close, then got outsmarted by McConnell and his side, and we all raced to the press gallery as McCain marched in to keep up the public pressure.

He was relentless, and ultimately successful.

In my youth and naiveté, I thought that was how the Senate actually works — like it is supposed to. Legislate, negotiate, pass a bill, make a bipartisan law.

Of course, watching McCain’s other big legislative battles, especially immigration reform on which he spent more than a decade working with no law to show for it, I soon learned that was not the case.

A sense of history

Another vivid memory is from the Authorization of Force debate after the September 11 attacks.

Senators were going back and forth with drafts of the resolution language, and I remember at one point early on, seeing McCain in the hallway and asking what he thought.

He looked at me and said at the top of his lungs with an “are-you-kidding-me?” look on his face, “We can’t accept this! Don’t you remember the Gulf of Tonkin?”

I had learned about it in history, but of course, McCain had lived it.

President Johnson used the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, passed after US ships were attacked in the Pacific, to send troops to Vietnam and escalate the war without declaring it. It was a war that McCain fought in as a naval aviator until he was shot down and held as a prisoner of war for more than five years. McCain spent a lot of time at the Naval War College after he was finally released studying how the civilian and military leaders had gotten things so wrong in Vietnam. He knew the answers. The Gulf of Tonkin helped set things in the wrong direction.

And then there was the issue of torture. There is nothing more powerful than watching a man get so passionate in the hallways talking to us reporters that he wants to raise his arms, but he can’t because they were broken so many times during brutal beatings when he was a prisoner of war. Now imagine him doing that while arguing against America’s use of torture after 9/11. That happened more times than I can count during his crusade to get the Bush administration to stop the practice of enhanced interrogation tactics with terror suspects. He said he knew from being tortured himself that they didn’t work.

And more importantly, that is not how America acts, despite the raw fear after the 2001 attacks.

Covering McCain’s 2008 presidential bid

When I was first assigned to cover the Republican presidential race in 2007, that meant covering John McCain. He was the next in line, and at that point that mattered in the GOP. He built up his war chest. He amassed a big campaign. He was the guy to beat, just as George W. Bush was in 2000.

Until it collapsed.

GOP primary voters, already skeptical of McCain, did not like his support for the Iraq surge, and more importantly, his support for a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants — legislation he worked on with liberals like Ted Kennedy.

I remember doing a story one night about the right wing coming after him, and I had interviewed a couple of conservative characters who had long been McCain opponents. The next day he saw me in the hallway and ripped into me. How could I give air time to people who make a living off of tearing apart the GOP, never mind the country. I don’t think it was the first time I was yelled at by McCain, which I later learned was a rite of passage, but it was the first time I remember feeling his wrath to that extent directed at me.

Ten years later when I sat in the Senate chamber watching McCain speak after returning from brain cancer surgery, his warning to colleagues to stop paying attention to talk radio and people who profit off of division took me back to that McCain tongue lashing.

Eventually, McCain of course climbed back to win the 2008 GOP nomination, and I was on the road with him full-time. It was an experience of a lifetime to cover a presidential campaign start to finish. At first, he ran the campaign the way he did in 2000 — with freewheeling discussions with reporters on his bus and his plane. But as the general election really took off, that stopped. His aides tightened it up and tried to stay on a message a day, and letting their candidate answer questions all day long didn’t allow for that.

I sensed McCain missed the more chaotic atmosphere, but I also understood that he felt a bit betrayed by the press. He had been the one reporters liked to cover, and now the focus was on the history making candidate on the other side. To be sure, those of us who followed McCain day in and day out tried to play it straight with every story, but it was impossible for McCain to escape the reality that Barack Obama generated the excitement and drew the giant crowds.

I remember the day Obama made his big speech in Germany before tens of thousands of people. McCain counter programmed by going to see George H.W. Bush at his home in Maine. It was a terrific visit for those of us in the press because the former president, ever the gentleman, showed us all around the Kennebunkport compound. But when it came to pure imagery, it was McCain and Bush on a golf cart riding around in Maine, up against Obama speaking to a sea of people at the Brandenberg Gate. There is no question it was tough for McCain.

And then there was the Sarah Palin pick.

What I remember as much as the dysfunction internally about a series of disastrous Palin interviews that undermined McCain’s ready-to-be-commander-in-chief platform, was the brewing strain of intolerance in the McCain-Palin crowds. We all remember the famous moment in Minnesota when McCain took the microphone away from a voter who called Obama an “Arab.” But leading up to that was a lot of consternation about signs appearing at McCain’s rallies and people in the crowds heckling with racist undertones. He hated it. He tried to stop it and that culminated with that town hall moment. That was because it was already clear to McCain something was happening in the base that he did not like, and that was the backdrop for his extraordinary concession speech urging his supporters to back Obama, marking the moment in history for the country despite his loss.

I remember standing on the press riser at the Biltmore Hotel watching him deliver that speech on election night 2008 and thinking how remarkable it was, but I only now realize how truly extraordinary it was through the prism of today’s times.

Just a few of his lessons

Despite the complexities of the man, what his death means for America is even more complex. Sure, he was an American hero. Yes, a war hero. He was a conservative who fought for smaller government yet revered the institutions of government and democracy. He was passionate about his beliefs, but also understood the art of compromise for the greater good.

He had a unique voice. He knew it and he wasn’t afraid to use it. He was an unofficial ambassador for America for decades, traveling the world trying help dissidents fighting for freedom and basic rights and believing to his core that America has an obligation to use its power.

I am forever grateful to McCain for teaching me to be serious without taking myself too seriously, to have meaningful debates and discussions without being mean, and to learn early on how to run through the Capitol hallways in heels, because that was the only way to keep up with him.