(CNN Money) — This week, almost a full year after the election of Donald Trump, Facebook, Twitter, and Google are testifying before house and senate committees examining the role that social media — and Russian manipulation of it — played in the 2016 elections.

Much of the focus around Russian meddling and social media has centered on Facebook, which was the first to announce that it had found evidence of the campaign on its network.

The Internet Research Agency, a troll farm in St. Petersburg with ties to the Kremlin, ran hundreds of pages designed to look like activist groups in the U.S., and bought thousands of Facebook ads on divisive issues like race, religion, LGBT rights, and gun rights.

Though members of Congress will no doubt have questions for representatives of Twitter and Google as well, the majority of the focus could well end up being on Facebook, both because of the company’s dominance and because of the scale of the Russian operations on its site. Facebook itself estimates that 126 million people may have been exposed to content created by the Russian pages.

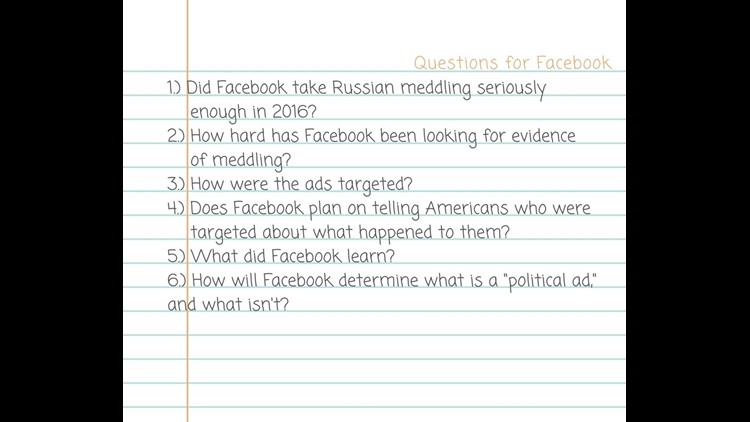

Representatives from the three companies appeared before the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism on Tuesday. On Wednesday, they will appear before the House and Senate Intelligence committees, each of which have been investigating Russian meddling for months. Here are some of the questions that Facebook’s general counsel Colin Stretch may be asked Wednesday — many of which could also be asked of Twitter and Google.

1. Did Facebook take Russian meddling seriously enough in 2016?

“I think the idea that fake news on Facebook … influenced the election in any way is a pretty crazy idea,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said shortly after last year’s election.

So, with that quote in mind, members of Congress will likely want to know: Did Facebook take the threat seriously enough? Could the reach of Russian operations have been curtailed or even stopped if Facebook had taken the threat more seriously?

Facebook’s answer may be, at least in part, that it didn’t know about the threat because the government never said anything about it. But Facebook was informed after the election. The Washington Post has reported that soon after Zuckerberg dismissed the “fake news” factor as “crazy,” President Obama pulled him aside at a conference in Peru to warn that unless Facebook addressed the problem, it would be even worse in 2020 election.

2. How hard has Facebook been looking for evidence of meddling?

In September, Facebook handed over to Congress records related to the thousands of ads and hundreds of Facebook accounts it has found that were designed to meddle in U.S. affairs.

Since then, CNN and other news organizations have reported that many of these accounts were operated well after the presidential election was over, with some even remaining active until they were shuttered by Facebook in August.

All of these pages, Facebook says, were from one Russian troll farm, the Internet Research Agency. Members of Congress will likely want to know how Facebook found these pages, and how difficult it was to find them. They’ll also want to know how sure Facebook is that there are not other Russian troll farms running similar pages, and how confident it is in its own ability to find such content.

3. How were the ads targeted? Did the targeting match that of official campaigns?

Facebook’s ad-targeting technology allows advertisers to tell Facebook what kinds of people it wants to advertise to — that is, target — based on things like their age; where they live; their political interests; and, up until after the election, their race.

Facebook will know where in the U.S. the Russians targeted their ads and when they did that targeting — for instance, whether people in swing states were targeted the week before Election Day, or whether the targeting wasn’t that specific or sophisticated.

There’s also a more complex but potentially more important issue here. Facebook should be able to show if any of Russia’s ad targeting matched targeting by official campaigns in the U.S. If the troll army were targeting the same people in the same location that a candidate or PAC was, this could warrant further examination.

4. Does Facebook plan on telling the Americans who were targeted by the Russians, or who engaged with content produced by them, about what happened to them?

In testimony prepared for a subcommittee to which Stretch will testify Tuesday, Stretch discloses that 126 million Americans may have been exposed to content generated on its platform by the Russian government-linked troll farm, and that 11.4 million saw ads from the group.

Congress is due to release the Russian ads Facebook provided to them. But there are millions of people out there who may have seen or interacted with or even been influenced in some way by what the Russians did, and the vast majority of them are probably in the dark about that. Is anyone ever going to tell them what happened?

5. What lessons did Facebook learn from Russian operations like this in other countries?

After the extensive scrutiny it got regarding elections over the past two years, Facebook has said it is doing better on this front. It has, for instance, said that it removed thousands of fake accounts in advance of this year’s German and French elections — though it didn’t say if these accounts were Russian.

But Facebook has not provided all the answers on the question of foreign elections that members of Congress might want. Just last week British lawmakers asked Facebook to provide details of any Russian-linked ad buys around the Brexit referendum in June, 2016, and last year’s UK general election. (Facebook said it would respond “once we have had the opportunity to review the request.”)

The committees could ask how effective Facebook’s efforts in Germany and France truly were, and how its experience fighting fake accounts in Europe could help stop the spread of the same in the U.S.

6. How will Facebook determine what is a “political ad,” and what isn’t?

In September, Zuckerberg announced that Facebook would begin requiring disclaimers on political ads — a policy that it went to the Federal Election Commission to seek an exception from in 2011.

But determining what qualifies as a “political ad” can be tough.

Sure, if an ad comes directly from a campaign, it’s pretty clear cut. But the Russian ads at issue here would not for the most part have fit under the common definition of a political ad — they didn’t call for anyone to vote for or against a specific candidate. It’s not just the Russian ads that are a potential can of worms either. What if your friend, who isn’t involved in a campaign, decides to spend $100 promoting a New York Times article that reflect positively reflects a candidate and target voters in her neighborhood. Is that a political ad? And how will Facebook detect it?

7. How many people at Facebook will be working on monitoring political ads?

Facebook said last week that pages running federal election-related advertising in the U.S. may be required to provide documentation to verify what organization or campaign they are part of and their location.

Facebook says it is developing automated tools to help with this process, but verifying the identities of ad buyers and determining the nuances of political ads will likely require some human moderation. Lawmakers would be justified in asking how much money Facebook might put behind that effort, and whether it will be enough to really do the job.

8. Will Facebook continue to embed with political campaigns?

Facebook, Google, and Twitter have in the past provided staff to embed with major political campaigns to advise those campaigns on how to effectively utilize their ad platforms and target voters.

Embeds from the tech giants act as “quasi-digital consultants to campaigns,” researchers from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the University of Utah, found.

Nu Wexler, then Twitter’s Policy Communications Manager (he’s now with Facebook), said of Twitter embedding with the Trump digital campaign, “One; they [the Trump campaign] found that they were getting solid advice and it worked, and two; it’s cheaper. It’s free labor.”

Some members of Congress may well ask whether Facebook and its competitors plan on continuing this quasi-political consulting role.